From hardship to heritage: The story of Saba’s lace-making women

Ingenuity in the face of hardship is a prevailing theme for many countries and territories in the Caribbean.

And Saba despite its small size and peaceful atmosphere, is no exception to that trend.

In fact, being ingenuitive was how Saba’s women were able to create a lucrative cottage industry that allowed them to provide a better quality of life for their families from the 1880s and well into the 1900s as their male counterparts left the island to work at sea.

What industry is that you might ask?

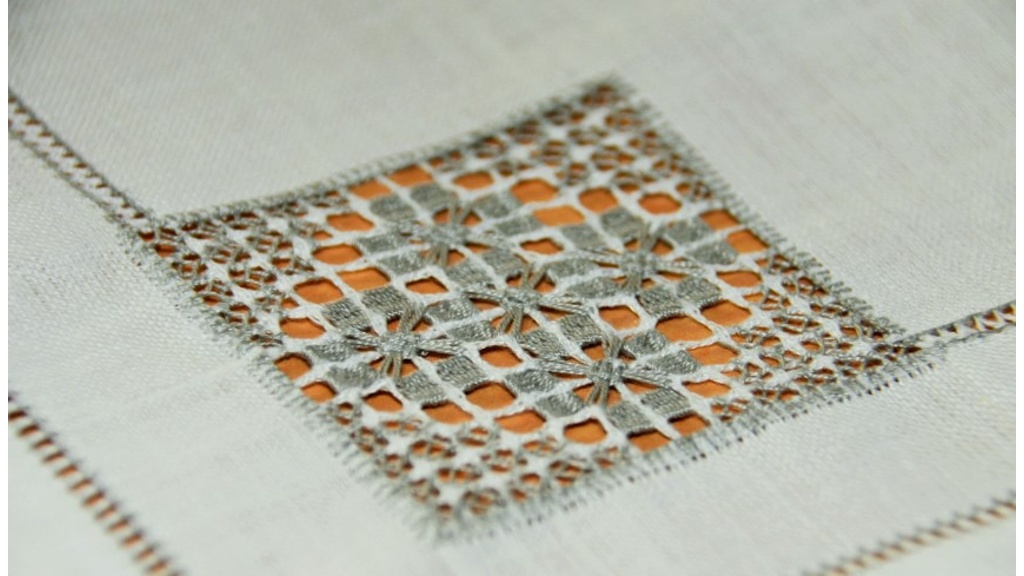

Saba’s unique, masterpiece threadwork earned the island its first nickname “The Island of Lace” since it became a hot seller worldwide—particularly in the United States.

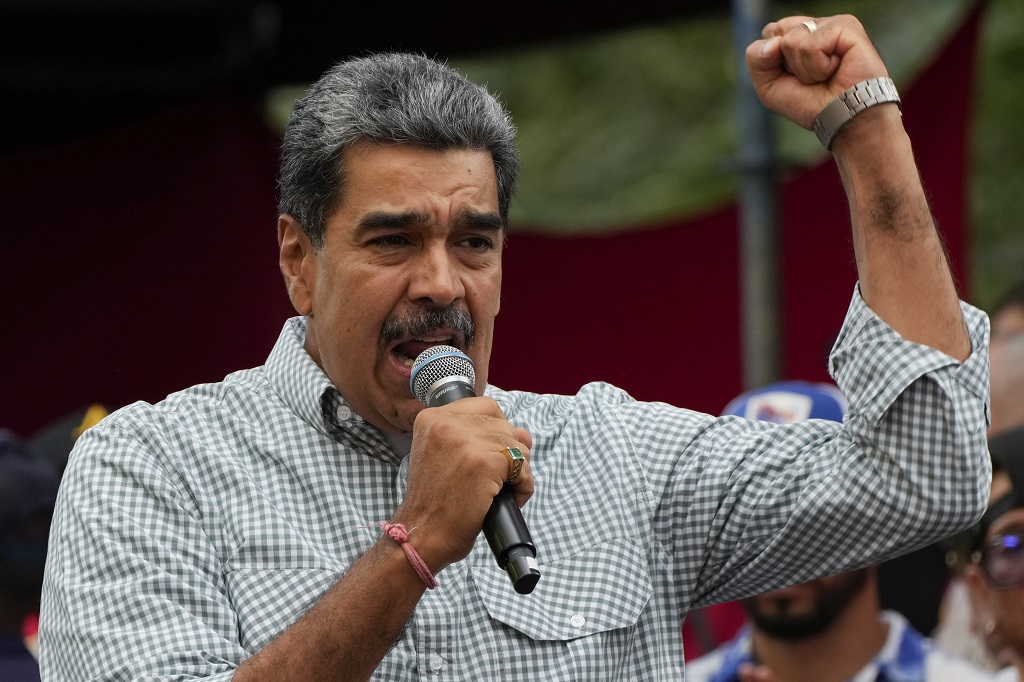

Saba Lace, sometimes called “Spanish Work”, was introduced to the island by Mary Gertrude Hassell Johnson when she returned home after learning the craft during her schooling at a convent in Caracas, Venezuela.

Johnson passed on her knowledge to a few women and the cottage industry was born.

In the early stages, the women created their elaborate pieces and the men would sell them during expeditions to neighbouring islands.

When the mail service established a frequent connection with the outside world in 1884, the industrious Sabans pounced on the opportunity to diversify their fortunes outside of what was provided by agriculture and fishing.

Without any clients, the brave and entrepreneurial-minded women wrote to merchants to enquire about selling their products internationally.

After writing several letters, the women got their big break.

From the first delivery, Saba Lace earned a reputation for being of the highest quality, allowing a thriving mail-order business to be established.

The insatiable appetite for Saba lace on the international market helped the cottage industry to become the island’s main export.

During the 1950s, sales to Americans alone earned Saba over US$15,000 annually.

At the height of interest in Saba lace, over 250 women were involved in crafting the thread work and each artisan had her own unique pattern.

These patterns were passed on from mother to daughter and each generation refined the masterpiece to please a modern client.

But with all things, Saba lace soon entered a period of decline, and threadwork was replaced by eco-tourism, with education being the island’s main source of revenue.

But the entrepreneurial spirit continues to be kept alive by a few women, who make up the famed Lace Ladies group, and their work is available for purchase online.

From baby bibs to pillows, doilies and Christmas tree ornaments, there is something for everyone on the website.

National pride is a prevailing theme in many of the creations on sale today.

Additionally, books have been written to celebrate the hard work of Saba’s pioneering women.

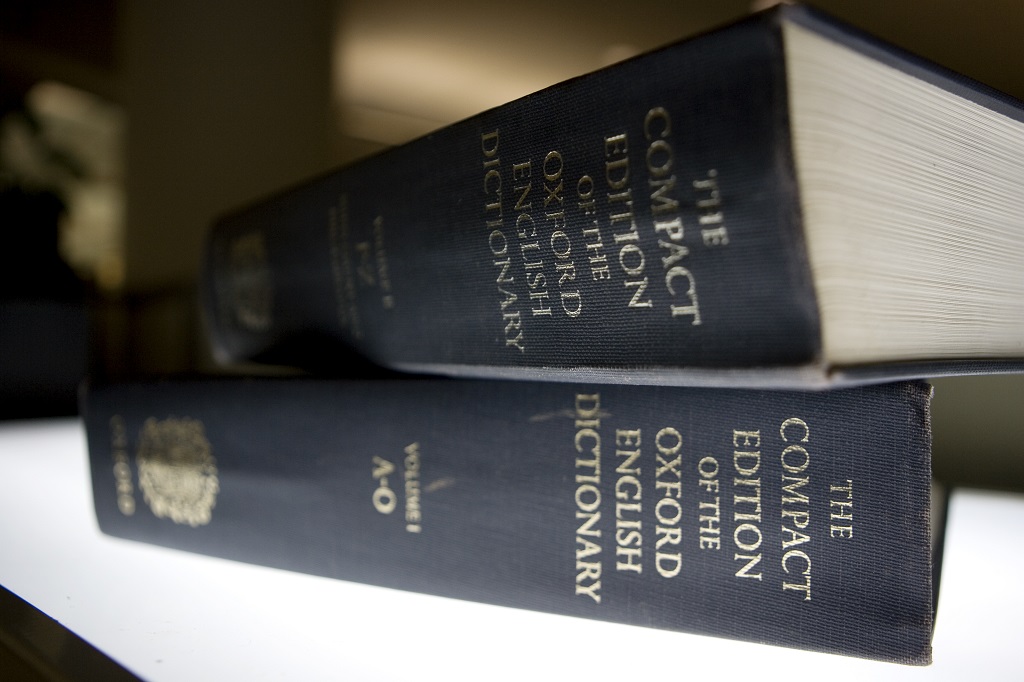

American Eric Eliason wrote a book titled “The Fruit of Her Hands: Saba Lace, History & Patterns” and it is listed as a “bible” for Saba lace as it includes a wide history of the trade and includes a variety of lace patterns that would have gone extinct.

His second book “The Island of Lace” takes a deeper dive into the importance of lacework to Saban culture, economy, and history.

It includes over three hundred photographs from famous documentary maker Scott Squire of the last remaining lace workers.

If you have an opportunity to visit Saba, keep the heritage alive by purchasing at least one of the fine-crafted lace products.